Hello, friends, and welcome to the first issue of Once Upon a Book, a newsletter about picture books, children's literature, and children's book illustration.

A while ago I found myself wondering about the origins of Stone Soup, that classic tale about generosity and coming together as a community. Over the last several years, in the United States, where I live, it has felt like both qualities have been on a steady decline, and it has been all too easy to feel discouraged and disconnected in the face of a fracturing society. Might the Stone Soup story help bolster the spirits?

The essential details of the story go something like this: A traveler arrives at a remote town or farming community. The traveler asks for food from the town's inhabitants but they, being mistrustful of strangers, rebuff him. Undeterred, the traveler sets up a cauldron of boiling water, drops in a rock, and declares he will make a "stone soup" and entices the townspeople to contribute various ingredients until a delicious soup is cooked up in the end with enough for all to share. The townspeople and the traveler eat and celebrate together with a newfound sense of goodwill and shared community.

Surprisingly, given how widespread the story is, a quick Google search didn’t turn up much information about the provenance of the tale. The most complete history has been gathered by William Rubel, an expert in traditional foodways and, fittingly enough, a founder of Stone Soup magazine. According to his research, though Stone Soup probably originated as a folk tale, the earliest recorded version was written by a Frenchwoman named Madame du Noyes in 1720 but with no mention of the story having been orally told to her. The central theme of Madam du Noyes's and other written versions of the 18th and 19th century versions centers around good-natured trickery: the town or farm folk are fully aware that they are being "tricked" into giving up their larders for the stranger's soup, but it's an equitable exchange since the process of making the soup is fun and entertaining and results in a tasty meal for all

Beginning in the early 19th century, the Stone Soup tale moved quickly to America. Rural America being, at that time, more prosperous relative to much of rural Europe, the conflict between an empty-handed traveler and an equally impoverished community would not resonate with American readers, so it was changed to center around greed vs. generosity, with the economically comfortable but stingy townsfolk learning a moral lesson about generosity at the end of the tale. According to Rubel, the plot and moral themes of most modern retellings of Stone Soup come from this Americanized version stemming from the 19th century, with the definitive picture book retelling penned by Marcia Brown in the 1950s.

I was particularly interested in the change, over time, from a trickster tale to one used to teach a moral lesson, and from the framing of the conflict shifting from one between two groups of have-nots to between two economically unequal groups. Are all modern retellings essentially the same, I wondered, or would there still be some variation in theme?

The children's librarian at our local library helped us track down five versions of the story that the library had on its shelves, and they were all such interesting takes on the Stone Soup story, each reflecting or expanding upon a different facet of the tale's original motifs, that I decided to present them all here.

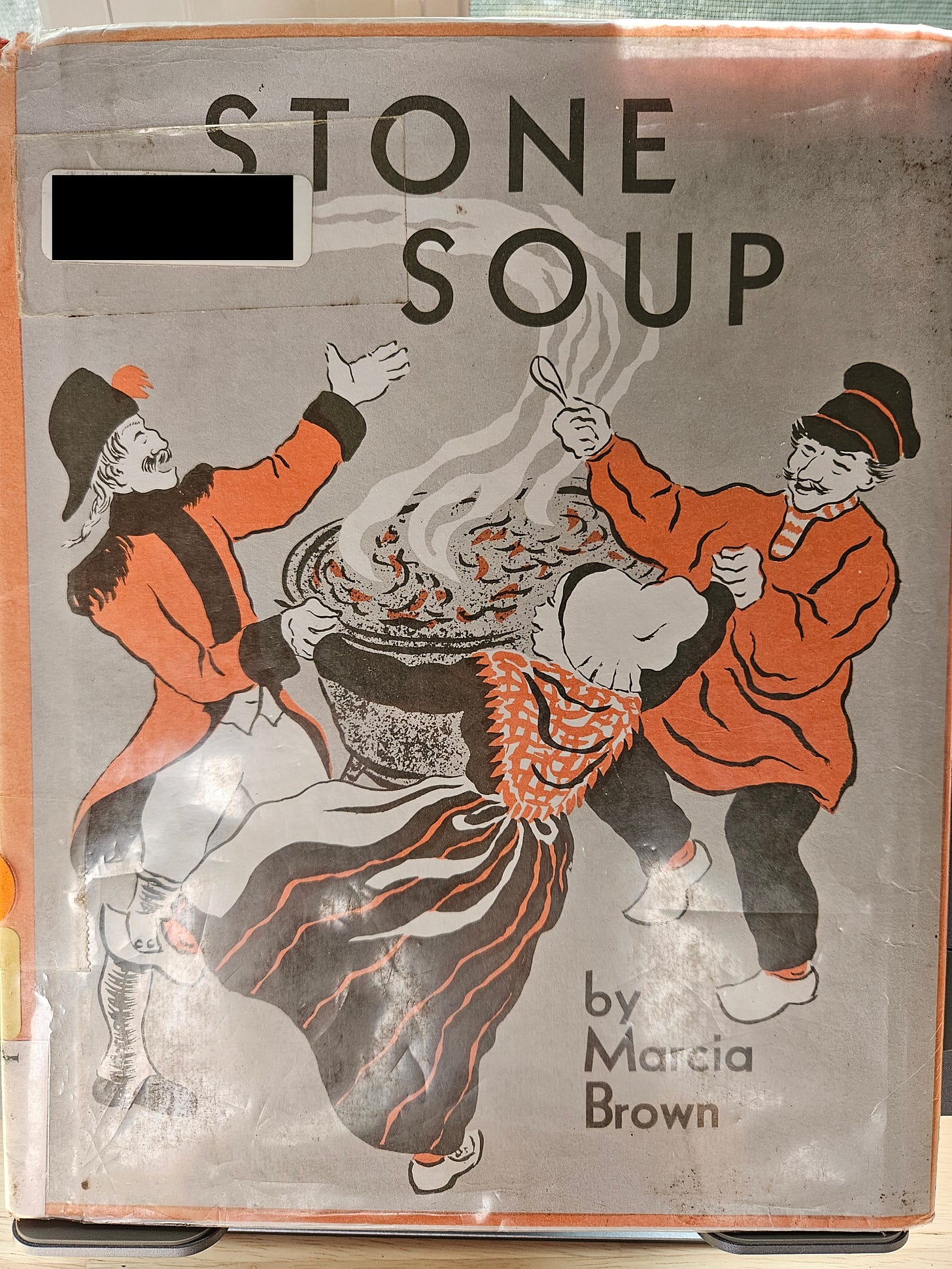

Stone Soup, written and illustrated by Marcia Brown (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1947)

Three soldiers, famished and tired, wander the countryside after a war. They come upon a farming village and go door to door to beg for food. The mistrustful villagers, however, tell themselves that times are hard, and hide their food away in rafters and chests to avoid having to give away their meager supplies. In response, the soldiers set up a cauldron in the town square, boil water in it, throw in a stone, and proclaim about the wonderful soup they could make if only they had the right ingredients, such as carrots, cabbages, and meat. Beginning with the village children, little by little the townspeople are lured out and persuaded to contribute to the pot until a truly wonderful soup is made to be shared by all.

Marcia Brown's retelling popularized the stone soup tale as a children's story and is widely acknowledged as the standard storybook version on which most modern retellings are based. While the basic arc of the story remains the same, some small but significant details have been changed. The travelers of the original French tale have been changed to soldiers, and Brown, an American, introduces a thematic dissonance between an American moral lesson about generosity and a vaguely European rural setting that is presumably struggling with food scarcity.

This version is the archetype for modern retellings, and for good reason. Brown's prose is straightforward and lively and her illustrations, rendered in a limited palette of reds, browns, and black, are expressive and exude a gentle humor. Even if you already own another version of Stone Soup, if you enjoy the classics then Brown's retelling is definitely worth adding to the collection.

Fandango Stew, written by David Davis and illustrated by Ben Galbraith (Sterling, 2011)

This version is a delightfully creative riff on the traditional tale. Davis ditches the European setting entirely and places his version in Texas in the Old West. Slim and grandson Luis, two vaqueros (cowboys) ride into the town of Skinflint. They are hungry and tired from having ridden through the desert, but the townsfolk aren't eager to welcome them. Undeterred, Slim and Luis persuade the blacksmith to at least lend them a giant cooking pot, which they set up in the town square and fill with water to boil. Instead of the traditional stone, Slim throws in some fandango beans and slyly convinces the townsfolk to contribute the remaining ingredients. In the end, Slim and Luis whip up a delicious fandango stew and the Skinflint residents come together for food and celebration.

Of the versions I checked out, this one was the most narratively and thematically cohesive. Davis really leans into the American Old West theme and corrects the balance between hungry travelers and stingy townsfolk. The characters who turn Slim and Luis away are the town's mayor, the banker, the sheriff, in other words the social and economic elite of the town, making the lessons of generosity and collaboration more organic and harmonious than they were in Brown's version.

I also loved the detail that Davis and Galbraith pay to the smallest details. Even the vegetables are no longer generic, but instead specific to the region: peppers, squash, and okra in addition to the usual carrots and cabbage. Ben Galbraith's illustrations, modeled firmly after the style of Lane Smith and beautifully composed, make full use of the Old West setting, making Fandango Stew the most visually exciting version of this group.

Fox Tale Soup, written by Tony Bonning and illustrated by Sally Hobson (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2001)

This is an animal version of the Stone Soup story. A hungry fox asks for food at a farmyard and is rebuffed by the farm animals, so it rustles up a cauldron and a stone to entice the unfriendly creatures into creating a (vegetarian) stew, which all the animals share at the end.

Aside from Sally Hobson's charming illustrations, there is, unfortunately, almost nothing to recommend about this version. Bonning tells the story straight, with no modification except to the characters' species, and Hobson's illustrations dutifully describe the text without adding anything interesting to it; thus both the starting and ending points to this version are "Stone Soup but with animals," and Bonning's specific choice of animals pushes the story into the realm of the nonsensical. If the contrast between stingy human villagers and the hungry soldiers is odd, the characterization of farmyard animals uncharitably rebuffing a hungry fox is downright weird. Why should the chickens not turn away a predator, after all?

A book like this demonstrates why you cannot just substitute alternate characters and settings into a well-known tale without giving at least some thought into crafting a believable contextual framework for it all to hang onto. With a different cast of animals or even the addition of an explanatory line, this retelling might have come together in a way Fandango Soup does. But as it is, the overall effect is simply one of bafflement. With so many excellent retellings to choose from, there is no reason to settle for a lesser one.

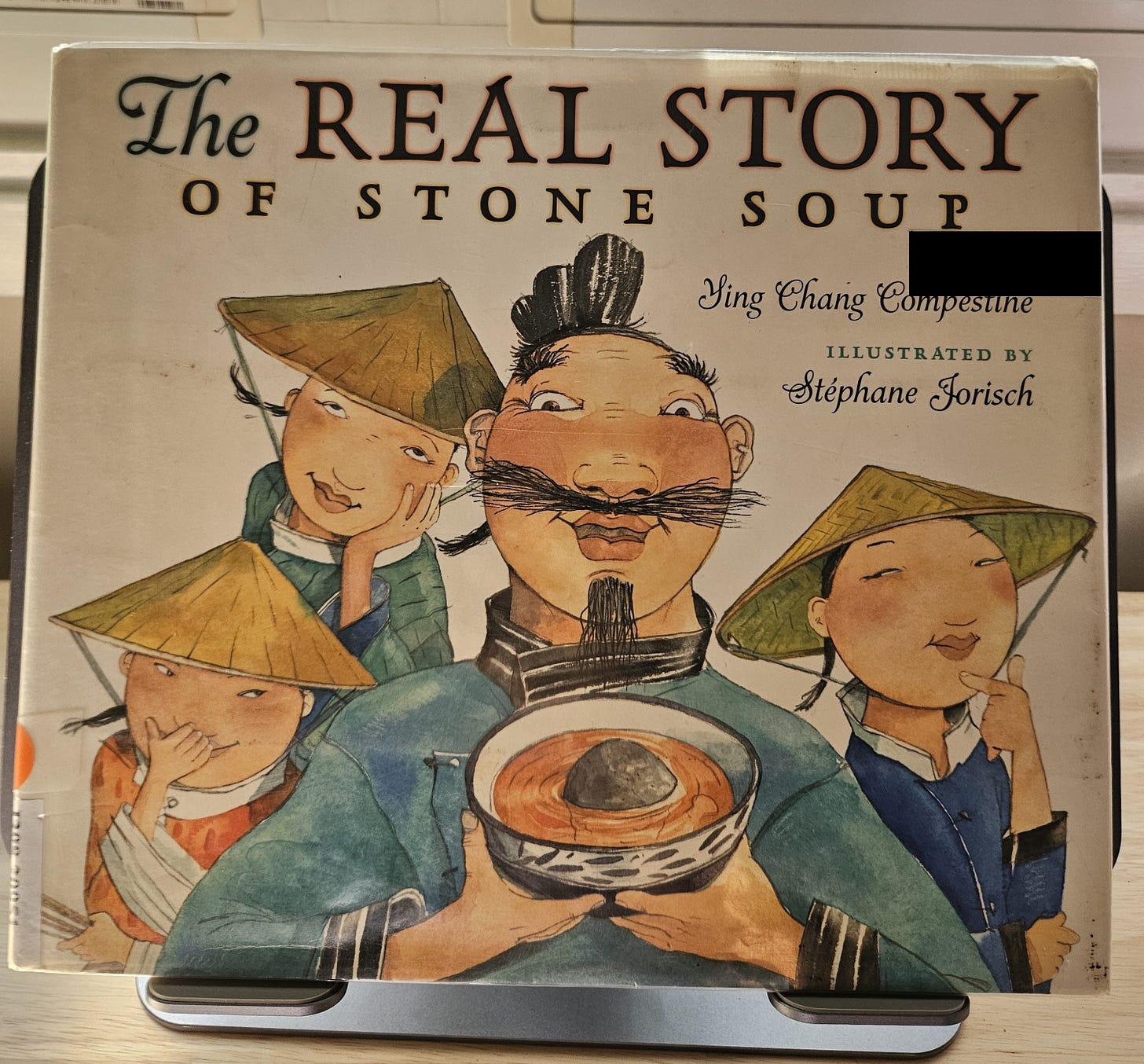

The Real Story of Stone Soup, written by Ying Chang Compestine and illustrated by Stephane Jorisch (Dutton Books for Young Readers, 2007)

The most inventive take on the Stone Soup story, this retelling is set in historical southeast China. In an inversion from the traditional European tale, this story is told from the first-person narrative of a foolish and self-important merchant with three young assistants, all brothers. The group go on an expedition to an island one day but discover they have forgotten to pack lunch. The three brothers tell the merchant not to worry and, to the merchant's mystification, begin digging a hole in the sand, then line it with leaves and fill it in with water. The merchant continues to scoff at the supposed foolishness of his assistants as they add stone after stone into the water, all the while assuring him that they are whipping up a scrumptious stew and all the while secretly adding in real ingredients behind his back. In the end, everyone shares a delicious meal - but has the merchant really learned his lesson?

One thing I really enjoyed was Compestine's riff on using stones to heat up soup, which is a real method of cooking soup ingredients in many parts of Asia. On a trip to Taiwan, I enjoyed a fish soup prepared with this method by an aboriginal chef - it was one of the tastiest dishes I'd ever eaten. As for my son, BB, this was easily his favorite book of the batch we borrowed from the library. As we read the story out loud together, he practically cackled with each turn of the page, delighting in the brothers' hoodwinking of a foolish adult.

Compestine puts several other spins on the original story. Instead of centering on a trickster protagonist, the story is told from the perspective of the person being tricked, who is himself an unreliable narrator. While the characters nominally all contribute to the stone soup, no moral lessons are learned by the end of the story: the merchant, believing that he did the lion's share of the work, remains just as self-centered and arrogant as before. The pleasure of this story comes from its comical tone and masterful harmony between text and illustration. While the merchant recounts his thoroughly dubious story, Jorisch's lively watercolor paintings show us what's really going on.

Though clever and funny, I wouldn't consider this a "real" stone soup story. It has in common stones, soup, and a bit of harmless trickery, but it lacks the moral lesson that makes the stone soup fable a universally resonant tale. This is less a criticism than an observation. If you are looking for a more traditional take on the stone soup story or one that emphasizes community and generosity, this may not be the version for you. But this book is an excellent addition if you are looking for a humorous story that will help develop a child's skill at grasping a story's meaning from both textual and illustrated narratives.

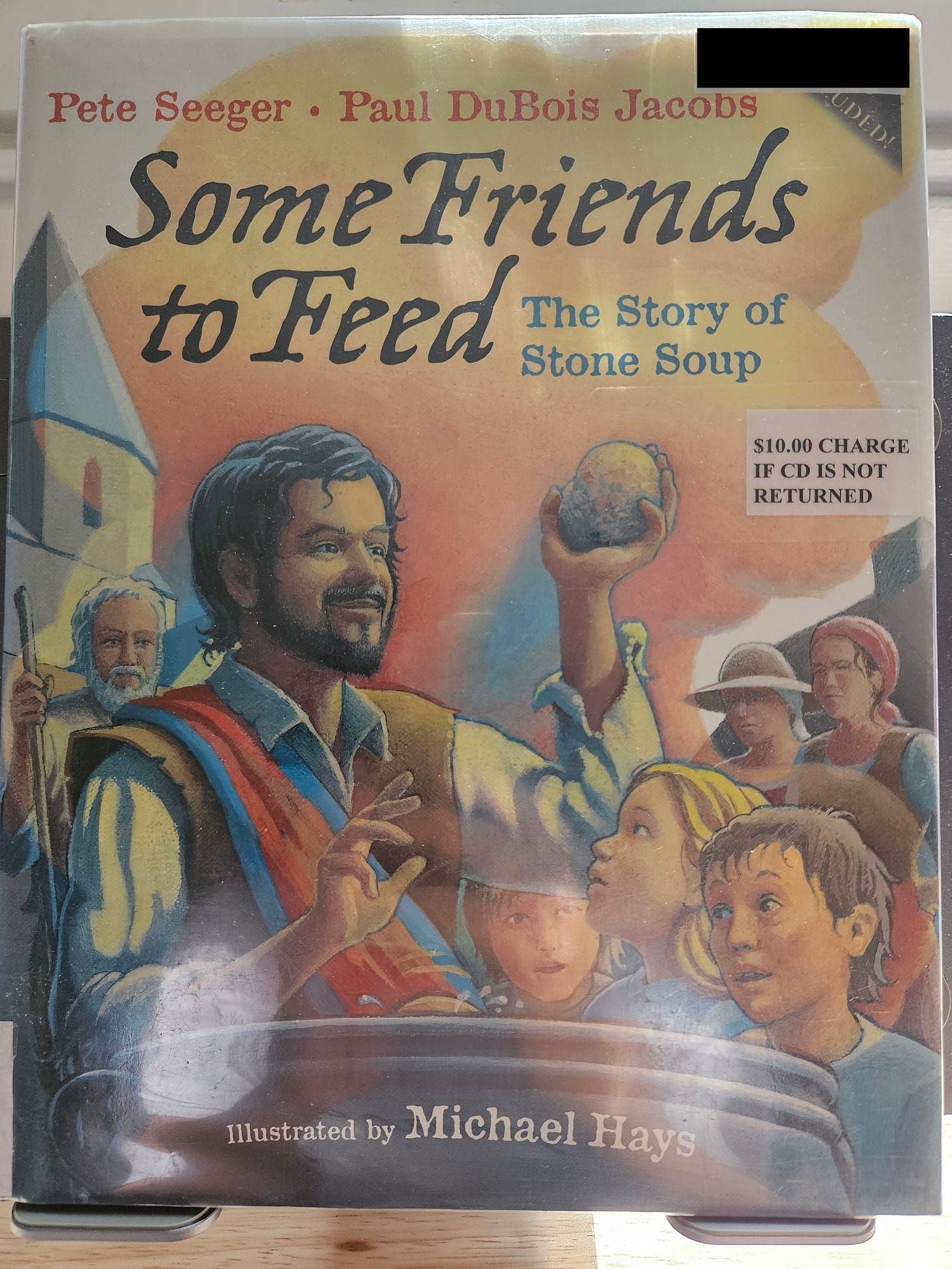

Some Friends to Feed: The Story of Stone Soup, written by Pete Seeger and Paul DuBois Jacobs and illustrated by Michael Hays (G.P. Putnam's Sons, 2005)

In this retelling, Pete Seeger and Paul DuBois Jacobs takes us full-circle to a more traditional take on Stone Soup. A war has ended and famine has invaded the land in its aftermath. A hungry soldier enters a village and begs its residents for food. The villagers, distrustful of soldiers and hungry themselves, shut their doors against him. Following the familiar tale, the soldier sets up a cauldron of boiling water in the town square, drops in a stone, and entices the villagers to come together to make a soup that can be shared by all.

Unlike other, more socially benign versions, Seeger and Jacobs riff on Marcia Brown's conflict between soldiers and villagers and envision the characters suffering from famine following a war. This detail lends poignancy to the tradition of having child characters, the innocent victims of war, being the first to offer ingredients to add to the soup. I really like the use of this spin to gently signal a pacifist message. It feels very true to Seeger's legacy of commitment to civil rights and war protest causes, and at the same time brings an age-appropriate focus onto the sociopolitical conditions of scarcity that drive the conflict between the soldiers and the villagers in the original tale and which has omitted in many modern retellings in favor of a simpler moral about sharing. Don't get me wrong, learning to share is an important lesson for children to learn, but all the same, good for Pete Seeger for going there.

Social messages aside, Seeger and Jacobs' prose is lyrical and a pleasure to read out loud. Michael Hays' beautiful illustrations, with its use of bright, almost sunlight colors, provide a hopeful contrast to the grim setting of the story. As an added bonus, the book comes with a CD featuring an original song that Pete Seeger wrote to accompany the story. You can watch a video of the book, narrated by Seeger, on Michael Hays' website.

I love these comparisons -- so interesting! The version I had when I was a child myself, by Ann Mcgovern, will always hold a special place in my heart -- the illustrations were so vivid to me, I've carried them with me into my adulthood -- but I think my favorite version, now, is Quill Soup by Alan Durant. It's a riot of color, and a pleasure to read and absorb.